Part 2 – Play within the city

The previous entry to this blog was an invitation to enjoy our cities, play with them, change the meaning of the objects and spaces around us. A couple of readers kindly noted that (COVID-19 regulations aside) doing such a thing may represent a challenge, particularly if we consider different socio-economic dynamics embedded into the city and define how we interact with these diverse spaces and their inhabitants.

The essence of these comments was beautifully captured by Charles Dickens in “A tale of two cities” a couple of centuries ago, when claiming: “I see a beautiful city and a brilliant people rising from this abyss, and, in their struggles to be truly free, in their triumphs and defeats, through long years to come, I see the evil of this time and of the previous time of which this is the natural birth, gradually making expiation for itself and wearing out…” thus making us wonder what are the evils of the previous time and today? Who are these brilliant people, and what kind of abyss are they rising from? And while I am not talking about rising from an actual abyss, this analogy could easily apply to the limitations for us to fully play within our cities. How deep down are we in the chasm of fears that prevents us from exploring our cities as spaces of play? In what ways can we shine and rise as individuals thoroughly enjoying our right to the city?

If something characterizes the French Revolution and its pursuit for equality, liberty, and fraternity, is its plight to recognize that human beings are all born equal and have the same rights to fulfill their needs and lead thriving lives. It does not surprise that Dickens’ strong criticism of social inequality and skirmish by it ensued are set against this background. “A tale of two cities” (Dickens, 1859/2003) is set between London and Paris. The first is dull and cold; it is a place that represents conservationism and stiff upper lips towards any notion of social change. The latter is “the city of lights,” where flaring passions and continuous cries for change and egalitarianism keep society on the brink of chaos and confusion, up to the point that the violence and social anger take over reason, making people act against the very same values they are fighting for. Sticking to the book’s descriptions, back then, play in both cities would differ: if in London, using the street for something outside of the rules, would be scolded; if in Paris, the streets had so many functions that play was just one of its many social frills.

Despite the picturesque differentiations between its inhabitants, traditions, and what both cities represent, Dickens shows an ongoing, pervasive social struggle, generalized unhappiness, and overall disappointment in life due to socio-economic inequality at all levels. Not everybody had the right to their city and, if translated into today’s societies, the criticism depicted in “A tale of two cities” is not far from the reality that millions of people face every day, everywhere in the world.

The freedom to play in a city, as the notion of an inclusive city that allows the fulfillment of all its citizens’ needs, is an optimistic wish because “the socialization of society and generalized segregation” (Lefebvre, 1968/1996 pp.157) is real, palpable. Urban apartheids keep evolving (Ladiana, 2017), exacerbating segregation that, itself, is not a spatial mirror of a social structure rather “another expression of inequality that, under some conditions, can have an influence on increasing social differences.” (Leal, 2012). The inhabitants of cities -everywhere in the world- are always warned by others (verbally and through media) about not going to the “wrong side of the city,” the “dodgy” sides. Invariably, the question that follows is: what determines the “wrong” and the “right” sides? Would it also be “wrong” to play there? Having a “wrong” side is undoubtedly a limitation to waste the accumulated human energy in play wherever individuals feel like exercising their rights to the city.

Location, location, location…

It is expected that by the year 2030, 60% of the world population will be living in cities. If no action is taken, by that time, 3 billion people will be living in slums or shantytowns (UN stats, 2020). The existence of informal settlements hampers the development of safe, equal, and inclusive societies while shifting the relationships between citizens and the city.

The tale of two cities is no longer about two different geographical locations but of areas within the same topographical space; and there are not two, but many cities within, with gates and fences physically delimiting many of these areas. Each micro-city has its own dynamics and characteristics, although both sides share the same wall and gate. The definition of “in” or “out” depends on where one is standing. For the economically affluent gated neighborhoods, “in” means decent living conditions, access to services (from water, public transport to education opportunities) – “out” means to face the “off-putting, discomfiting, vaguely threatening, rough life” (Ladiana, 2017). Slums and ghettos are defined as “low-income enclaves” spaces where economically vulnerable population concentrates (Kelly, 1995). The main differentiator between both is that the latter is tied to groups of the same culture. Affluent gated communities are called “golden ghettos” (Álvarez-Rivadulla, 2007) despite that the economic means to afford living in that part of the city may be the only thing their inhabitants have in common. From the Bow Quarter in London to the enclosed compounds at the edge of the national wild park in Nairobi, these walls are justified as means of “safety,” although they are mere representations of fear (Brunn, 2006).

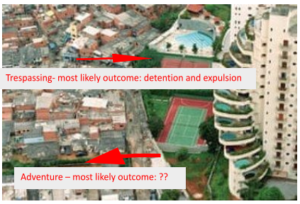

The consequences of playing with fear, this is, acknowledging there is a risk inherent to going behind the walls yet claiming the right to the city to play there, can be dire. If it is from a low income to a higher-income community, the game is called “trespassing” and can end up with the players spending a couple of nights in jail. Playing from the opposite direction (high-income end willingly adventuring into the low-income one) can be seen as an “adventure,” and it offers a more varied set of possible results: from surprise and complete indifference to unexpected interactions with the locals (Fig 1)

Photograph of Paraisopolis and Morumbi neighborhoods in Sao Paulo by T. Vieira

It may appear that with so many fences around and more emerging, the right to the city, this spatial entity for equal, democratic relations and integration, is gone; however, the right to the city is finding its way to overcome these barriers through play and creativity. In some cities, slums are turning into recreational areas and expressions of art. In Brazil, the “bailes da favorita” are parties at the favelas, where local youth, young wealthier Brazilians, and foreigners dance the night away (Brown, 2017). Also, the walls of slums all over the world are becoming canvases, opening more spaces of play to provide colorful and insightful messages that help to dignify the living conditions of its inhabitants besides improving the aesthetics of the city (Art in slums, 2012; d’Allant, 2017; Rayomand, 2018).

Of course, these examples of play within the city are barely scratching the surface of a deeper, systemic interaction between power, human rights, and even the fulfillment of our fundamental needs. A more nuanced reflection on how we are consuming our cities through play (or is it that cities are consuming us in a not so playful manner?) will be part of next quarter’s blog.

If we think about how attainable it is to play within the city regardless of the fences we face, either physical or intangible, let’s remember what Monsieur Ernest Defarge (a wine shop owner turned French revolutionary) noted “Is it possible! Yes. And a beautiful world we live in, when it is possible, and when many other such things are possible, and not only possible but done.” (Dickens, 1859/2003)

About the author

Georgina Guillen (Ginnie) has devoted the last twenty-something years of her life to the ambition of making sustainable development happen. After crafting and implementing projects for the private and not-for-profit sectors, she is currently exploring the fascinating world of gamification as a member of the prestigious Gamification Group at Tampere University (Finland), facilitating the creation and exchange of knowledge between the disciplines of Gamification and Sustainable Consumption, particularly in cities.

References

- Álvarez-Rivadulla, M. J. (2007). Golden ghettos: Gated communities and class residential segregation in Montevideo, Uruguay. Environment and Planning A, 39(1), 47-63.

- Art in Slums (2012). Diverse entries. Art in Slums blog. https://artinslums.wordpress.com/

- Brown, S. (2017, October 23) Top Favela Parties in Rio De Janeiro. Culture Trip. https://theculturetrip.com/south-america/brazil/articles/top-favela-parties-in-rio-de-janeiro/

- Brunn, S. D. (2006). Gated minds and gated lives as worlds of exclusion and fear. GeoJournal, 66(1-2), 5-13.

- D’Allant J. (2017) How Art Helps Slum Residents in the Global South. The Huffpost. www.huffpost.com

- Dickens, C., (2003). A tale of two cities. London, England ; New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. Originally published in 1859.

- Flanagan, M (2009) Critical Play: Radical Game Design. MIT Press.

- Kelly, M. P. F. (1995). Slums, Ghettos, and Other Conundrums in the Anthropology of Lower Income Urban Enclaves. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 749 (1 The Anthropol), 219–233.

- Ladiana, D. (2017). Urban dystopias: Cities that exclude. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 12(4), 619-627.

- Leal, J. (2012). Residential Segregation. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home (pp. 94–99). Elsevier.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996) The right to the city, in Kofman, E.; Lebas, E. (eds.), Writings on cities, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell (pp 147-159). Original work published in 1968

- Rayomand, E. (2018) Are Slums Dark and Dangerous? This Artist Is Using Paint to Change Your Mind. The Better India. https://www.thebetterindia.com/132477/misaal-mumbai-art-slums-rouble-nagi/

- UNstats (2019) Sustainable Development Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-11/

- Vieira, T (November 29, 2017) Inequality…in a photograph. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com