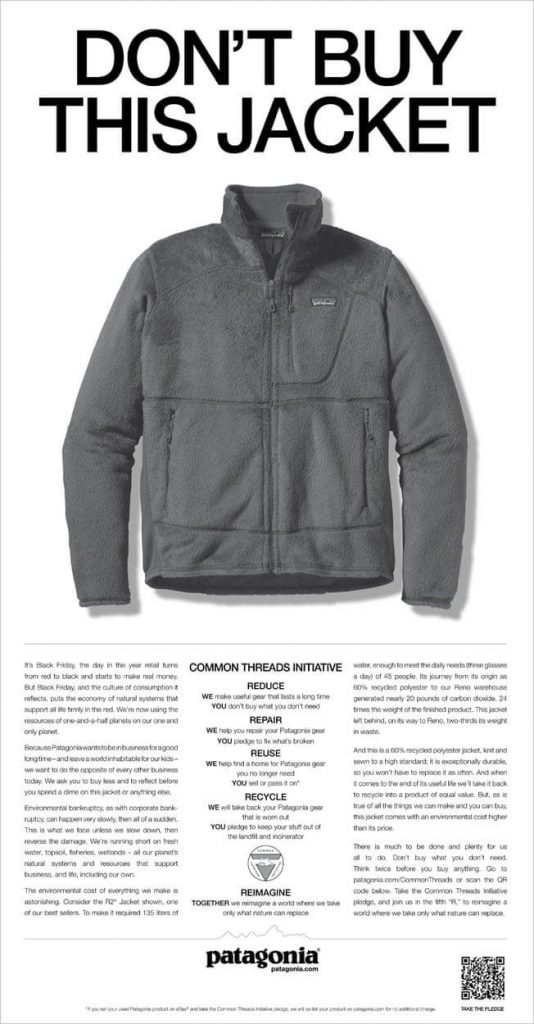

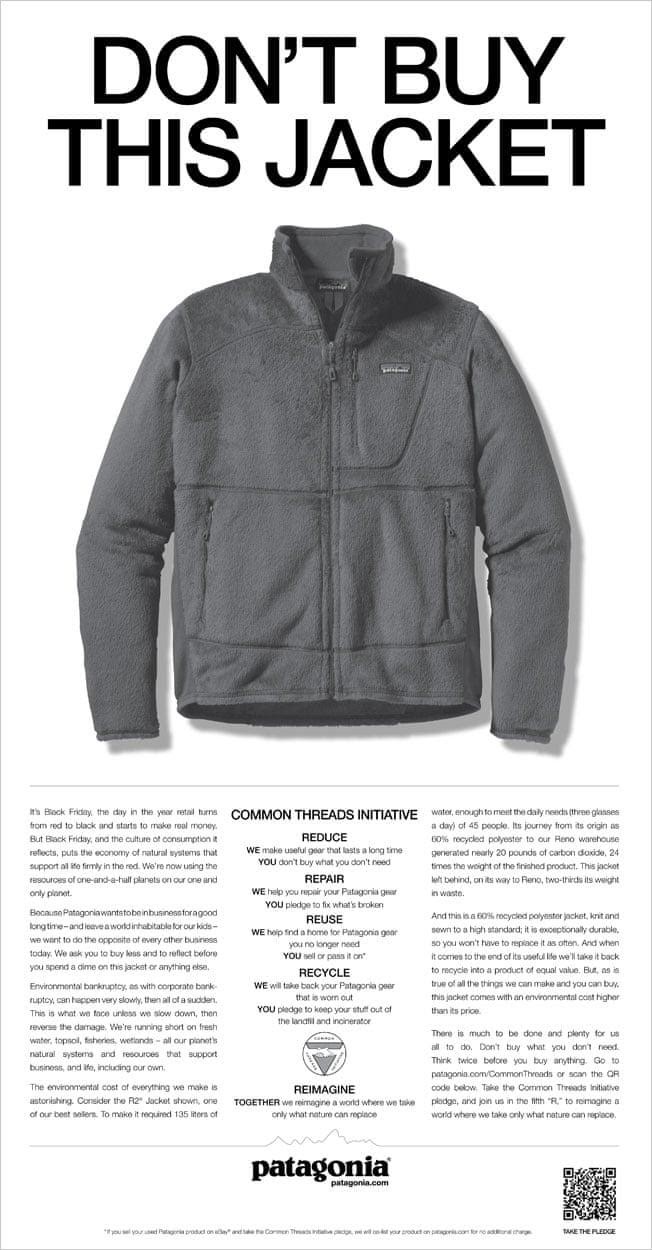

In 2011 Patagonia, a multinational medium-size corporation specializing in high-end, technically advanced outdoor equipment and clothing, posted a curious ad. Above a picture of its popular jacket, the ad says “Do Not Buy This Jacket”; and the extensive accompanying text, rather than listing the alluring attributes of the jacket, discusses environmental impacts of its manufacturing and Patagonia’s efforts to minimize those. It even talks about the craziness of the Black Friday shopping frenzy. Amazingly, the sales of the jacket increased by 30%. It is impossible to know if the ad was just a marketing ploy directed at the people who want to feel good about their purchases and who prefer hiking in the wilderness over shopping, or if this was a genuine effort by the company CEO and founder, Yvon Chouinard, to educate customers about the ecological cost of their shopping habits. In either case, the ad was remarkable in that it drew attention to the issue of unnecessary and excessive consumption.

Based on an article by Marissa Meltzer which not long ago appeared in the Guardian and aptly titled “Patagonia and The Northface: saving the world – one puffer jacket at a time” (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/mar/07/the-north-face-patagonia-saving-world-one-puffer-jacket-at-a-time), I lean toward the latter explanation. Founded in the early 1970s, and still privately owned as a for-profit B-corporation (B stands for social benefit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B_Corporation_(certification)), Patagonia has distinguished itself in various rankings and on many counts. Its two and half thousand employees rave about its working conditions, advancement opportunities, family friendliness, and benefits. The company avoids malls, locating its stores in places that mean something to the community, pays strict attention to the behaviors of its supply chain, carries no debt, and prides itself in paying its fair share of taxes. It also tries to use only organic cotton and torture-free goose down, and it has tried to replace as many of its synthetic materials as possible with recycled ones. These are largely possible because of the absence of shareholders.

What is not to like? Can we call Patagonia a sustainable company? Well, here are two paradoxes. The popularizing of outdoor culture and wilderness that is the basis of Patagonia’s sales pitch exposes these places to hordes of people who will eventually degrade them. Furthermore, the company’s success, as measured in growth of revenues and gross sales, is fundamentally based on growth of sales. The stuff may be produced in ethical ways, and that is very important, but from the perspective of consumption and consumerism, it is not sustainable. Chouinard recognizes these paradoxes and tries to compensate through the company’s otherwise socially responsible and ethical behavior, but he has to acknowledge “We’re going to make our product with the smallest footprint possible, but it is a footprint.”

The question of sustainable corporation is especially relevant today, as their power, reach and political self-serving are greater than ever, despite the three decade old Corporate Social Responsibility movement (CSR). A recent essay by Allen White, posted on the Great Transition Initiative website of Tellus Institute (https://greattransition.org/gti-forum/csr-white), recognizes the failure of this movement and looks for alternatives. The concept of CSR emerged in the late 1980s as a call for corporations to become more accountable to a range of societal stakeholders for their actions with respect to the environment, employees, communities in which they operate, and the society at large. It was definitely a soft call, built on the assumption that corporations can be incentivized to do the right thing by the threat of losing their social legitimacy. Without much evidence that it would work, the academics, regulatory institutions, and the media proclaimed it a panacea and fell in love with such terms as “corporate citizenship,” “shared value,” and “sustainable business.” In the spirit of neoliberalism, government regulations were replaced with voluntary standardized disclosure systems about corporate activities (full disclosure: I studied and published at length about the Global Reporting Initiative, the best known among such systems).

Today we know that this was a mirage. With the exception of extreme cases of malfeasance (e.g., Boeing and its 737 Max plane or Mylan and its EpiPen), corporations do not need to concern themselves with their social contract. In the financial capitalism of today the last word on social legitimacy belongs to Wallstreet and the powerful “rentier class” it represents. The performance disclosure schemes have become to many companies a public relations tool.

White and his commentators, representing a wide range of reformist thinking, call for alternative corporate governance systems and even a more fundamental redesign of corporate charters: a reinvention of corporations as forces for long-term social betterment. They focus on corporate governance more akin to the German, Austrian, Dutch, and Nordic model where employee and union representatives serve on corporate boards; on B-corporations, which like Patagonia are specifically chartered to balance the interests of multiple stakeholders: workers, customers, suppliers, community, and the environment; or on broad-based worker ownership altogether, as in cooperatives.

Holding back my skepticism, I can allow for the proposition that alternative business models will encourage some businesses to act in socially beneficial and ethical manner (if you believe in inspiring ethical behavior through institutional rules). These companies would, like Patagonia, not exploit their employees and the environment, provide fair wages and generous health, family, training, and retirement benefits, and allow for a democratic element in their governance.

But as long as they sell their products to consumers they would not be sustainable. When sales of consumer products is the basis of a company’s success it will always strive toward more consumption. And it matters little if it is an employee-owned cooperative, a privately owned enterprise, a B-corporation, or some other model. The best we can hope for, and here the example of Patagonia is instructive, is an ethical company that cares about social good.

In the end, I do not think that this is a depressing conclusion. It simply means is that if we want to advance a cultural change toward less consumption and consumerism, we should not count on companies, no matter how ethical, to be part of that movement. This job will have to be carried out by citizens-consumers, hopefully guided and incentivized by wise government policies. With respect to sustainable consumption, the “we all” in the oft heard “We are all in it together” does not refer to all the actors who created the current consumer society.