This quarter in Play (Q4)

The last month of the year usually comes full of reflections and resolutions, and, after a second year of uncertainty, partial or full lockdowns, unrest and fear, the prospect of a new year, may bring the hope that things will get better. Beyond COVID-19 related restrictions, playing within the city, may prove challenging due to factors that range from individual perceptions of public spaces, to socioeconomic differences that segregate entire communities that share a common, geographical space.

Some may say “these are times to take things seriously, we can’t play in the city as we used to. We are not safe”. The notion of safety, already introduced the previous quarter, opened up the discussion of how safety and play are connected, specially when looking into how we are consuming our cities, or consumed by them.

Taking into consideration Lefebvre’s definition of the “science of the city” and the need for creative activity (oeuvre); the increasing gated layout of cities seem to clash with the praxis of urban society that allows the ever-evolving nature of cities to become the areas where oeuvre can recover its meaning through the appropriation of time and space. From a capitalist, hierarchical point of view, it may look like the oeuvre is a need that can only be satisfied if other more “basic” needs, such as safety, are first fulfilled. However, if the “need” for safety is fulfilled by restricting access to certain parts of the city, the higher-level needs (like oeuvre) are unattainable.

About needs and rights

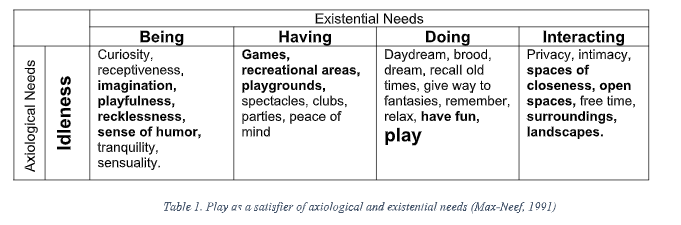

The right to the city emerges from the understanding that needs are not hierarchical, rather interrelated and interactive, systemic; they can be classified as existential -being, having, doing, interacting- and axiological – Subsistence, Protection, Affection, Understanding, Participation, Idleness, Creation, Identity and Freedom (Max-Neef, 1991). These needs are the same throughout cultures and times; what varies are the ways they are satisfied. Based on the existential-axiological need matrix (Table 1), play satisfies various needs, particularly for “doing idleness.” As a space for creative activity, the city satisfies the needs of having, doing, and interacting idleness. Recklessness, imagination, and playfulness, expressed as crossing fences to re-appropriate the city, are satisfiers for “being idle.”

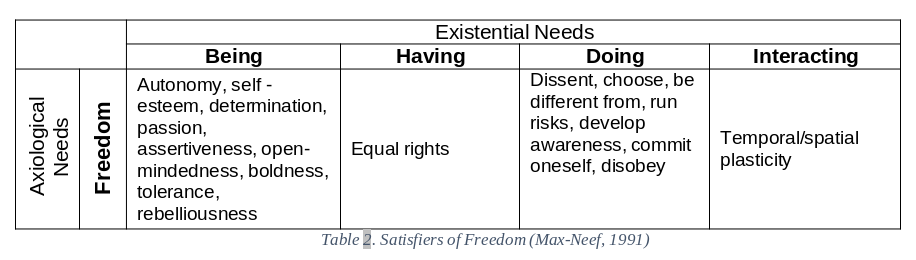

What about the needs of protection, creation, and freedom? Are not the gates and fences somehow satisfying these needs? The Human Scale Development (Max-Neef, 1991) presents living space, social environments, and dwellings as the satisfiers for “interacting-protection,” while spaces for expression and temporal freedom satisfy the need for “interacting-creativity.” As an axiological need, freedom is satisfied as shown in Table 2, and it is a reflection of the right to the city described by Lefebvre (1968/1996).

Satisfiers can be synergistic and singular as they may simultaneously satisfy various needs. It is also essential to acknowledge the existence of violators or destroyers, pseudo-satisfiers, and inhibiting satisfiers (Max-Neef, 1991). Fences for “protection and safety” are clearly a destroyer, as they “not only annihilate the possibility of its satisfaction over time, but they also impair the adequate satisfaction of other needs. These paradoxical satisfiers seem to be related particularly to the need for Protection. This need may bring about aberrant human behavior to the extent that its non-satisfaction is associated with fear. The special attribute of these violators is that they are invariably imposed on people.” (Max-Neef, 1991). This, of course, does not apply to the health measures requested to slow down spreading a mortal virus. In this case, we are acting towards fulfilling our needs for subsistence (being healthy) and protection (having a health system), not following these measures is undermining the possibilities of those around us to satisfy these needs. And we can still be very playful. The pseudo-satisfier of safety, comes in the shape of limitations to ourselves that, as expressed above, harm the satisfaction of over needs.

Gated communities are a reflection of “gated minds and gated lives” as individuals choose to be physically separated, retaining social and spatial distance from others, thus becoming “prisoners of space” (Brunn, 2006) Moreover, the power structures behind these gated layouts also hinder the right to the city and shape everyday life in the ways that Lefebvre (1991 – quoted at Flannagan, 2009) described as systems of consumption, surveillance, and property relations. This is, that play within the boundaries of one’s “right” side is also limited by another set of rules and power structures, where social relations are less driven by spaces of social equity and lived experiences and more by economic interests. The control over how and for whom urban space is created, essential for an inclusive city, is increasingly diminished by the proliferation of shopping areas as the centers of interactions (Ladiana, 2017). Our free time is being consumed by the notion that shopping is fun, that it can even “cure” us from emotional maladies or raise our spirits to celebrate. Is it really so? Shopping centers are also created to cater to a certain socio-economic group. Like with gated communities, if someone that looks like coming from a less-affluent community goes to a high-end mall, it is likely that the person will be spotted by the security cameras and be followed at all times. In some places even the color of your skin can get you profiled, ask laureate poet Amanda Gorman.

The ability to play in cities is always there, the capability to do so anywhere in the city not so much. For example, one may argue that the city’s physical limitations can be overcome through technologies that allow the creation of virtual spaces and immersive experiences like consuming personalized music (Bull, 2005). However, this is a resource mainly available to the inhabitants of the city’s side that can afford it; therefore, rather than providing a more equitable right to the city, these technologies widen the gap between sides. The challenge lies in making these technologies accessible to everyone, therefore providing equal access to these new spaces that transcend cities’ physical walls.

A (new) tale of many cities

It is naive to think that the social divisions may disappear for the sake of understanding human needs as a system, play as a satisfier and that cities can be magically re-appropriated for this purpose. However, it is not altogether impossible.

The oeuvre can be silenced with delusions of safety and stability, but it is a part of what being human means. Policymakers, business heads, and other social actors that shape power structures are also people. As such, they also can acknowledge the potential for social development that finding points of convergence between different types of players convey.

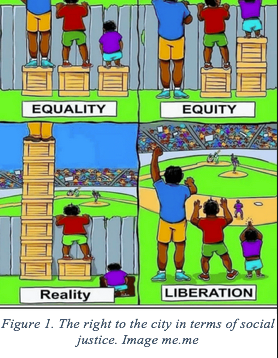

The advantages of liberating cities from fences (Fig 1) can be seen only when addressing the roots of the fear behind erecting these fences in the first place. Some first steps include the promotion of “landscapes of harmony”, cross-cultural and multicultural experiences, and “tearing down the walls” both physical and mental ones (Brunn, 2006). Artistic and cultural expressions, like a festival to showcase diversity make spaces for inclusion tangible.

Restituting the meaning of the oeuvre does not require a guillotine or expressions of violence, rather actions to allow creativity and play to ignite the desire to break the mold and find ways to shape a new reality for coexisting with other oeuvres. Awareness that the city belongs to all, and, as a common good is meant to be cherished, explored and transformed, is the first step to overcome the barriers that had scarred its surface.

The right to the city is a tale of every city. “A tale of two cities” (Dickens, 1859/2003) opens with a description that might as well reflect our quest to waste our accumulated energies in play. For some, today may be the best of times; for others, the worst. This spring of hope and winter of despair shows that, in the city, we have everything before, behind, and around us. It is possible to find agreements between different ways of play, create, or even recreate new spaces and relationships between citizens regardless of their side of the wall.

The real game to live the right to the city – or the renewed right to urban life (Lefebvre, 1968/2006) – at its fullest, is to find ways that everyone can play whenever and wherever wanting to do so (without limiting the right of others to play too). For the time being, this also entails playing with masks on, and keeping our distance.

About the author

Georgina Guillen (Ginnie) has devoted the last twenty-something years of her life to the ambition of making sustainable development happen. After crafting and implementing projects for the private and not-for-profit sectors, she is currently exploring the fascinating world of gamification as a member of the prestigious Gamification Group at Tampere University (Finland), facilitating the creation and exchange of knowledge between the disciplines of Gamification and Sustainable Consumption, particularly in cities.

References

- Brunn, S. D. (2006). Gated minds and gated lives as worlds of exclusion and fear. GeoJournal, 66(1-2), 5-13.

- Dickens, C., (2003). A tale of two cities. London, England ; New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. Originally published in 1859.

- Flanagan, M (2009) Critical Play: Radical Game Design. MIT Press.

- Ladiana, D. (2017). Urban dystopias: Cities that exclude. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 12(4), 619-627.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996) The right to the city, in Kofman, E.; Lebas, E. (eds.), Writings on cities, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell (pp 147-159). Original work published in 1968

- Max-Neef, M, (1991) Human Scale Development. Apex Press, Council on International and Public Affairs, New York, USA

- https://me.me/i/equality-equity-reality-liberation-ra-d9c92d8e4b454509a5b15bc651458cad