What if we applied Taoist and Zen wisdom to the coronavirus pandemic?

Many of you have probably heard the Taoist story of “May Be.” Also called “Who Knows What’s Good or Bad” and “The Farmer’s Luck.” If you haven’t, here it is: in text (below) and a 2-minute video version as well:

“An old farmer had worked his crops for many years. One day his horse ran away. Upon hearing the news, his neighbors came to visit. “Such bad luck,” they said sympathetically. “May be,” the farmer replied.

The next morning the horse returned, bringing with it three other wild horses. “How wonderful,” the neighbors exclaimed. “May be,” replied the old man.

The following day, his son tried to ride one of the untamed horses, was thrown, and broke his leg. The neighbors again came to offer their sympathy on his misfortune. “May be,” answered the farmer.

The day after, military officials came to the village to draft young men into the army. Seeing that the son’s leg was broken, they passed him by. The neighbors congratulated the farmer on how well things had turned out. “May be,” said the farmer.” [Reprinted from Zen Stories to Tell Your Neighbors]

The main idea, as Alan Watts notes at the end of the video version, is: “The whole process of nature is an integrated process of immense complexity. And it is really impossible to tell whether anything that happens in it is good or bad. Because you never know what will be the consequences of a misfortune. Or you never know what will be the consequences of good fortune….” In other words you shouldn’t overreact to any life event, good or bad.

Which David G. Gallan says even better:

“It’s not that the farmer is unengaged in life. It’s not that he is unable to be happy or sad. But he has a greater perspective. He sees the bigger picture. He knows that he can’t stop things from happening, but he can control how he reacts to them. And it’s often not the experience that matters as what you do with that experience.”

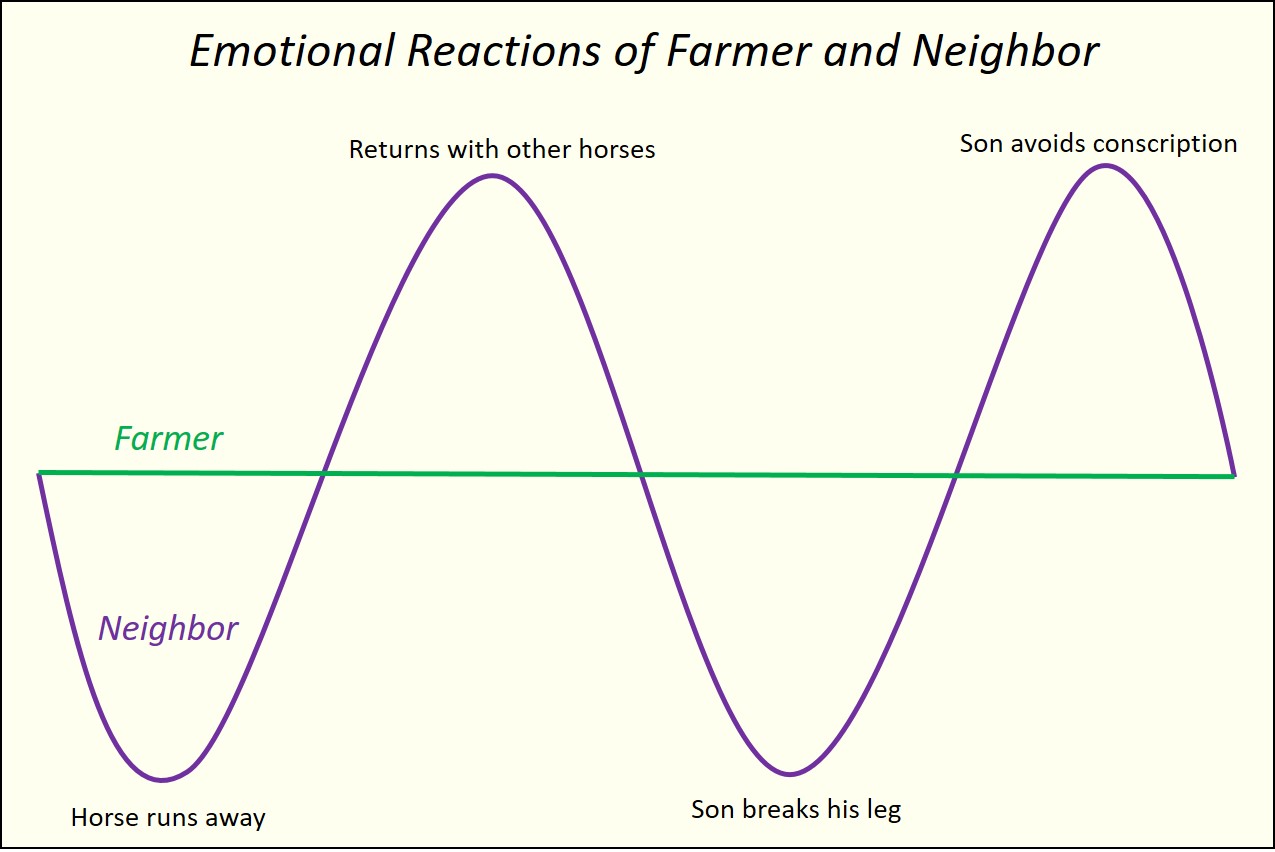

Gallan even includes a nice emotional graph of the farmer and his neighbor. They both observe the same things but the farmer reacts with equanimity to them—a graph I recreate below.

This is why “May Be” became such a valuable Zen story as well—reinforcing not just the key teachings of balance in Taoism but of non-attachment in Buddhism.

Of course, the way the story unfolds makes both lessons easy to understand and accept. If the farmer’s son hadn’t broken his leg but died taming the horse, would the farmer have remained as calm and accepting? Hard to believe he would, but that doesn’t nullify the lesson. There are many stories where great misfortune is a precursor for good fortune, where life balances out. My own father’s death in 2005—the single most crushing moment in my entire life—rapidly matured me and made me better understand what is truly valuable in life and what isn’t. Without his death, I never would have been open to meeting and marrying my life partner, who I met later that year, and which led to our wonderful son, and so on. (Of course, I shouldn’t get too attached to my family either—following these lessons—but I admit I’m less farmer and more neighbor, though I certainly try to be the former.)

Now let’s apply all this to our current coronavirus pandemic. I know that I, personally, have been on a rollercoaster of emotion, following the day-by-day developments of this pandemic, and I imagine many of you have been as well. It’s been far harder to tune out this media storm than others, whether that be the Trump administration, the Democratic primaries, or Brexit. Of course, it feels more life or death—because it is—and thus harder to tune out.

But are there ways to recognize that “May be” should be the response to every new development in this disease’s story? That our affect should stay flat like the farmer’s? It doesn’t feel as easy, but let’s go through the tale of “The Luck of the Virus” and give it a try.

The Luck of the Virus

A monk, after a long day teaching a meditation retreat, stands to stretch before retiring for the night. Before he can leave, one of the students—a news pundit from DC—comes up to him. “Teacher, what do you think about the novel virus that has erupted in China and is spreading quickly around the world? Isn’t it terrible?” “May be,” says the monk.

“But then again, it’s not so deadly and most people barely get sick. That’s lucky,” says the pundit. “May be,” smiles the monk.

“Though that means it spread far and wide before it was detected. That’s bad.” “May be,” replies the monk.

“On the other hand, our reaction has shown that when push comes to shove, we are able to put the public good over growth, individualism, consumer cultural demands—sports, jobs, tourism, even going out to eat. That’s amazing.” The monk sighs, “May be.”

“However, that reaction has crushed global trade, manufacturing, the service sector, and flying—disrupting hundreds of millions of lives—for weeks, months, even longer. That’s frightening.” Shuffling toward the door, the monk mutters, “May be.”

“But this has also reduced traffic fatalities by the thousands, and has reduced co2 emissions and other pollutants, which might mean millions of lives less affected by climate change in the future. That’s fantastic.” Edging closer to the door, the monk yawns, and once again says, “May be.”

“Yet the reduction in aerosol pollution might worsen climate change in the short term. That could be real bad.” Finally to the door, the monk shrugs his shoulders and says, “May be.”

“Then again the slowdown has shown that economic degrowth and a saner, less consumptive culture could actually be possible. Maybe this will prompt communities to rebuild their local economies.” Talking quicker and louder, the pundit continues, “This could even be the moment where we make true progress on climate change and sustainability. That’s good, right? Right, teacher?” “May be,” says the monk, before gently closing the door, leaving the student behind.

Just like with the farmer, the pendulum will keep swinging—though the monk may better screen students before his next meditation retreat.

No one can know what will come next in the development of this pandemic. Maybe the next verse will dwell on the economic and environmental rebound effects that come when advertisers and regulators spark a consumer orgy to catch up for lost growth. Then the verse after that hopefully will be that people, so sick of being prodded to consume, embrace simpler pastimes and realize they miss their public libraries, but not so much the crowded sports stadiums, and a new era of celebrating public goods and sharing starts.

Or perhaps the next verse will be a sustained depression, with millions out of work, which in turn sows political unrest round the world. But that might lead to many community and state level experiments with a post-growth culture and better provisioning of public goods. Only time will tell. The only thing we can control as individuals is our reaction to the developments. By detaching to a degree, and accepting whatever life brings, we can modulate our panic and joy and stay calm even as we navigate these frightening times.

And most importantly, we can apply this lesson to all of life’s developments, not just COVID-19. Climate change will bring tragedy after tragedy—but maybe these will bring good in their wake. Could Australians, after their devastating trial by fire make climate change a national priority? After droughts and floods decimate crops, could farmers lead the way to a sustainable agricultural transition? After cities are swept away by disasters, could people comprehend the threat and push for true changes that will reduce climate emissions and make our localities and countries more resilient?

May be.