I admit I have a problem with the term ‘local’. During the past years I have read and studied papers and scientific works on the environmental impact of what we eat every day. Food is one of the most important drivers of our environmental footprint and we are on the lookout for sustainable solutions. One strategy is to buy our products locally as much and as often as possible. When there is no valid alternative – for instance coffee or bananas, which don’t do well in our climate – we can resort to other strategies like buying organic.

Can-can

Here’s my problem: buying local as a means to reduce our environmental impact is a flawed solution. First, there is a lot of confusion around the term ‘local’. What is local in a Flemish (( Flanders is a region in Belgium which area spreads over 13.522 km2 and has approximately 6,5 million citizens.)) context, where I live, can mean a very different thing in France, which is almost 50 times larger and has more than 10 times as many citizens. In the absence of a clear definition, ‘local’ can have very different meanings: it can mean fresh (whatever that means exactly), it can be linked with organic farming or with a higher standard of animal welfare. It can mean a healthier product or a product with less packaging. Very often the term ‘local’ can mean fewer food miles and they can be products with a lower environmental footprint. ((Granvik, M., Joosse, S., Hunt, A. & Hallberg, I. (2017). Confusion and Misunderstanding – Interpretations and Definitions of Local Food, Sustainability, MDPI, Open Access Journal, vol. 9(11), pages 1-13, October.))

Notice the can-can in the previous lines. Buying local produce can be grown organically, but not necessarily. Buying local produce can be without less packaging, but it can be just as well the other way around. Just like ‘sustainability’, the term ‘local’ has shifting meanings. Does that mean that it’s rubbish? Not quite.

When is local, local enough?

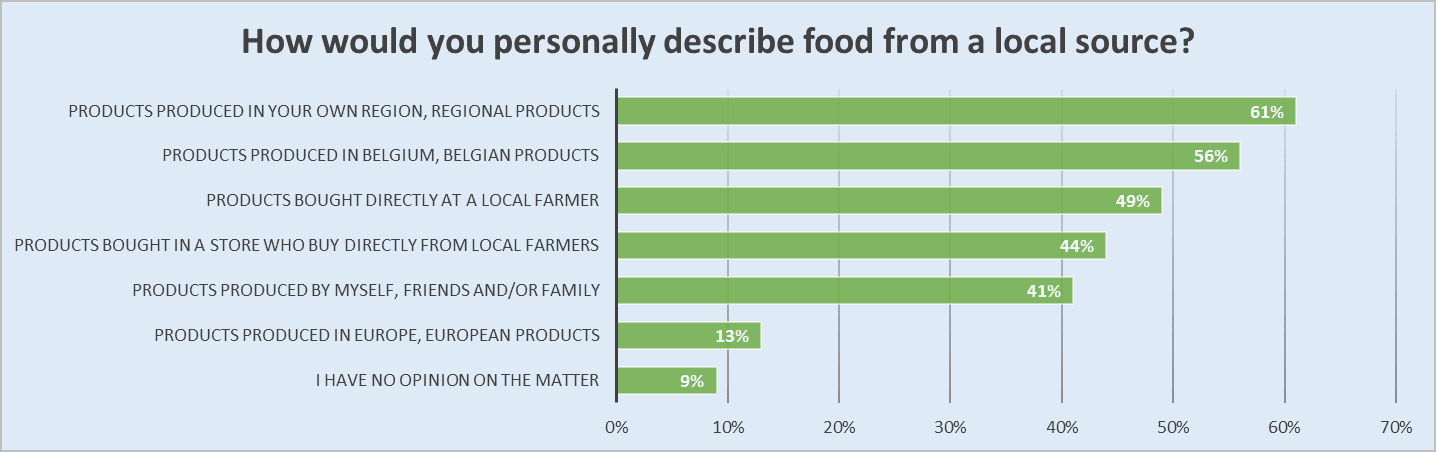

“Buying local reduces food miles and has thus a lower environmental footprint.” We found that the Flemish citizen values local sourcing pretty high when asked which actions they can take to reduce the environmental footprint. Sounds simple enough, doesn’t it? But where can we draw the line? When is ‘local’ local enough? We have asked our citizens in Flanders to give an indication when we can use the term ‘local’. ((Adapted from: GfK (2018). Milieuverantwoorde consumptie: monitoring kennis, attitude en gedrag, studie in opdracht van het Departement Omgeving, p. 113 (https://omgeving.vlaanderen.be/onderzoek-milieuverantwoorde-consumptie-monitoring-kennis-en-gedrag-2017-0 (Dutch only))))

Generally speaking, for the Flemish consumer ‘local’ means inside the borders of Belgium. There are some nuances, but it is clear that Europe is too broad as a geographical region to be considered local. Like in a lot of countries, our food comes from all over the place. So in the supermarket, it is a good idea to shop locally. Alright, that settles it! Or does it?

Count von Count

Every food mile avoided is a step in the right direction. There is some truth in this, but we need to look at the bigger picture. When we need to look at the total environmental impact of a product, we can rely on life cycle analysis (LCA). The word says it all, every stage in the life cycle of a product is taken into account and presents the most complete picture we can get. There is much to be said about the pros and cons of LCA’s, but often it is the best we’ve got. Just like Count von Count of Sesame Street, we need to count anything and everything (connected to the life cycle of the food product in question of course).

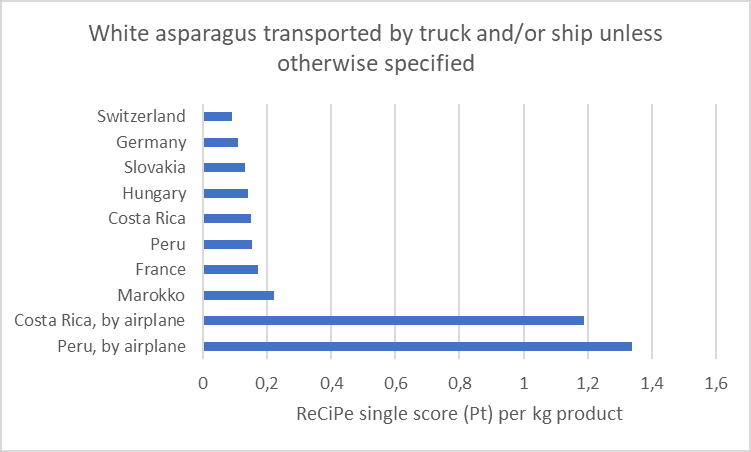

In general, the category ‘transportation’ ((Note that this disregards the way we as consumers make our way to the shop(s). When we move from farmer to farmer and then to the supermarket with our diesel car, the odds are that the avoided food miles were all for naught. )) accounts for three to six percent of the total environmental impact. ((Kramer, G. & Blonk, H. (2015). Menu van Morgen – Gezond en duurzaam eten in Nederland: nu en later, Blonk Consultants, p. 18)) There is one big exception though: transport by air. ((Clune, S., Crossin, E. & Verghese, K. (2017). Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories)) Very often highly perishable products or soft fruits are transported by airplane. So when they come from far away, chances are they are transported by plane. In some cases, the method of transportation is indicated in the supermarket. In the next graph the example of white asparagus ((This graph is representative for sales in Western Europe. Adapted from: Bergsma, G., Nijenhuis, L., Bijleveld, M. & Dalm, V. (2014). Goed informeren van Vlaamse consumenten over milieu-impact van voeding – Advies over voedselverlies, AGF en eiwitproducten – Van Eten naar Weten – Bijlagenrapport, p. 31)), which is in season right now, is shown. This example makes clear that the difference in environmental impact isn’t so much influenced by the country of origin. Take the case of an asparagus from Peru: the environmental impact of transport by air is roughly seven times higher compared to transport by truck and/or ship.

I’m not claiming that reducing food miles is insignificant, but there are other areas where we can make alterations in our food habits which have a far larger impact. In colder regions the production of vegetables – like tomatoes – often rely heavily on greenhouses. These require a lot of (fossil) energy while the same vegetables could be grown in countries with more favorable climatic conditions. The environmental impact caused by these greenhouses heated by fossil fuels is higher compared to the transportation by truck or ship. Combined with the unstable attributes with which ‘local’ is surrounded, it makes that claims like buying local food per definition contributes to a lower environmental impact are misleading and therefore do not make a good guideline.

A broader perspective

Again I raise the question: does this mean ‘buying local’ as a sustainability concept is rubbish and should be tossed in the bin? Not so fast. There are two ways other ways to look at this concept. The current food system is global and complex with a lot of actors in the whole chain. This has resulted in the fact that we as citizens and consumers have become more and more disconnected from where our food comes from. This leads to a decline in knowledge (in what month do we find cauliflower at its best? (( Starting from June!))

) and skills (how the heck do you prepare Tuscan kale? (( For those unfamiliar with this nutritious leafy vegetable, check some kale recipes by Ottolenghi. Do it. ))). Bridging the gap between the consumer and the farmer is an excellent way to reconnect with our food. This will lead to a higher appreciation of our food and the work put into it. We can expect that we will be less wasteful when we have a higher regard for these products.

Looking at this concept only from an environmental perspective is not enough. Of course there are other things at play. Supporting our local producers and suppliers is important, because they are an integral part of our societal fabric. The current COVID-19 crisis has disrupted the global food system and has laid its weaknesses bare. Maybe we should reevaluate our relationship with our food and where our food comes from. We even should consider local, small-scale farmers as an integral part to secure our food security.

Asparagus!

Looking from a strictly environmental point of view the advice ‘buy local’ is flawed because the avoided food miles represent a small fraction of the environmental impact of producing the food. What we consume has a far larger impact on our environmental footprint compared to avoided food miles (e.g. eating a more plant based diet). But looking at it from multiple angles produces a more convincing argument in favor of local. Head to the shops and buy the lovely produce from your local farmers. It is often in season and delicious. With all that spare time on your hands, let’s cook up some wholesome dishes! I’m off looking for some asparagus, it’s at the top of its game this time of year.

The author is a policy advisor for the Department of Environment and Spatial Planning of the Flemish Government and lives in Belgium and Switzerland. His views are entirely his own.